This post is a repost from my Patreon. Occasionally, I will republish essays that were once behind a paywall and make them available for free on my Substack.

Hidden in very few records is the true story of African rice on the continent. With the institution of slavery trying to dehumanize Africans, it became hard to fathom that Africans had such sophisticated processes of agriculture. But only in the last few decades has the world come to be reacquainted with African agricultural advancement. It is still largely unknown, but here is a story of Indigenous African rice.

Botanical History of African Rice

Rice in West Africa was domesticated as far back as 3500BC along the Niger River in Mali; centuries later, there were two secondary zones of cultivation in the Senegalese Casamance/Gambia regions and Guinean highlands. These resulted in three distinct forms of rice production-- flood plain tidal irrigation in the Sahel flood plain (where rice was first cultivated), rain-fed cultivation in highlands, and then irrigated systems in mangrove/marine estuaries.

Photo taken from Journal Article “African Rice in the Columbian Exchange” by Judith Carney

How was African Rice Unique?

When the Portuguese first ventured into the Senegal River, they noticed rice fields that relied on tidal floodplain cultivation, required sophisticated knowledge of tidal patterns, and an understanding of seasons to decide on seeding and transplantation of rice.

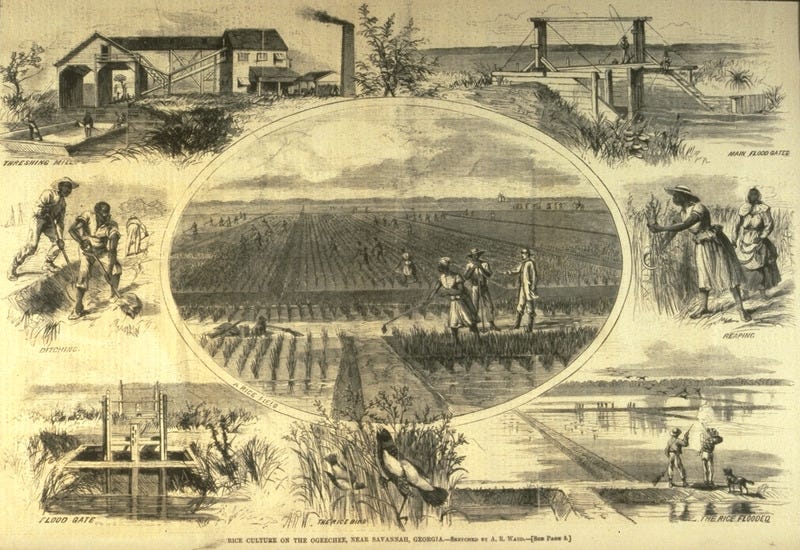

The most sophisticated of them all was mangrove irrigation systems. Mangrove irrigation rice required the transformation of the coastal land to support rice fields, using a system of dikes that directed water and captured rainwater. This method would have been applied by enslaved Africans tasked with transforming the swampy landscape of lowland Georgia and South Carolina into rice-growing fields.

The techniques described by early European accounts highlight various and specific tools, certain hoes, and the design of rice fields to grow rice at optimum amounts. These unique methods to cultivate rice underscore the sophistication of rice cultivation in this region of Africa.

Regardless of their distinct manipulation of the environment, many groups could apply different techniques to have an abundant and constant supply of rice. And that, they surely did.

How did slavery change the narrative of African Rice?

However, all this information was quickly lost. As Judith Carney succinctly puts it, “Slavery was not just about the appropriation of the body and its labour, but also of the knowledge and ideas held by enslaved human beings.” Slavery as an institution hinged on a contradictory premise – dehumanizing the Africans to justify slavery, but also selecting the enslaved specifically for certain knowledge and skills they had.

As the enslavement of Africans continued to increase at an exponential rate, it fundamentally changed African society and the food we eat. To justify slavery was to justify warping the image of an African from humans. The period of enslavement fostered more volatile relationships between once peaceful and cordial African groups. Many of these irrigation rice growers along the Guinea coast lived in decentralized communities, making them susceptible to enslavement and pushing them further inland. In parallel, they were also sought for their rice growing skills, being the labourers that undertook the massive transformation of swamps in the Carolinas, Georgia lowland, Suriname, and Brazil to rice plantations that were incredibly profitable.

“Rice Production on a Plantation near Savannah, Georgia, 1867” From Harper's Weekly (Jan. 5, 1867), p. 8 sourced from Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora.

Losing these people meant wiping out a sophisticated system of rice agriculture. In parallel, you have the introduction of crops from the Americas that yielded more within a short period to feed the massive cargo of enslaved Africans the white men stole, which also fundamentally changed the agriculture systems in this region forever, leaving African rice as less desirable.

Putting all this together, you have the erasure of a diversity of agricultural techniques leaving those that were rather simple (inland flood plain) and feeding into the narrative that Africans were incapable of such ingenuity.

Proper acknowledgement of African rice was given only in the 20th century when a French botanist started to compare the rice from inland (west of Sudan) to coastal West African rice and noticed that the two were distinctly different from Asian oryza sativa. Furthermore, the only documented introduction of sativa goes to missionaries resettling freed slaves in Liberia in the 19th century. Lastly, there were no existing documents that fully described the transfer of rice-growing knowledge from the Europeans to the Africans, especially as the Europeans took extensive notes.

African rice in modern times

Oryza Glaberimma has been added to a long list of African crops that are now termed underutilized and “lost”. Its production and processing in modern times have fallen victim to the same issues as many African industries, where a lack of resources and investments has made it less desirable. Free trade agreements and globalization have continued to push the growth of corn/maize and flooded our markets with polished Asian rice. But all is not lost, people continue to enjoy African rice in rural communities and use it for specific recipes that cannot be made with Asian rice. All hope is not lost.

References

Carney, Judith A. 1998. “The Role of African Rice and Slaves in the History of Rice Cultivation in the Americas.” Human Ecology : An Interdisciplinary Journal 26 (4): 525–45. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018716524160.

Carney, Judith A. 2001. “AFRICAN RICE IN THE COLUMBIAN EXCHANGE.” The Journal of African History 42 (3): 377–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853701007940.

Carney, Judith Ann. 2001. Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas. Cambridge, Mass. London: Harvard University Press.

Carney, Judith Ann, and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff. 2009. In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy in the Atlantic World. Berkeley, UNITED STATES: University of California Press. http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utoronto/detail.action?docID=488116.

My local ghanaian store carries this rice :) So truly all is not lost

So interesting. Thank you for this.